'Cause it was love

In all its agony

Every bit of me

Hurting for you.’

Spit of You ~ Sam Fender

A toddler sits in the dirt and in his hand is a rusty bottle top, but this is no ordinary bottle top. It’s a fast car, speeding down a windy road. “Bruuuuum,” the little boy growls, moving the car faster and faster, crawling forwards in the dirt to slide it along. Suddenly, he feels a sharp pain, and he leaps to his feet like a startled kitten. A broken piece of glass glints in the sun and his dusty knee now drips with blood. A cut has opened up on his tiny kneecap, a gaping slit in the virgin envelope of skin. John starts to cry. He stumbles to the shed at the bottom of the garden of the house on Arthur Street, the shed which is home.

It’s 1953 and John is three years old. In the shed there are two more children, both younger than him, and in a few years, he will be the eldest of six. By then, the council will have moved the family to a two-bedroom council house in the west end of the town. But for now, there is only the shed and the shame.

John’s mother Hazel cleans the knee up as best she can, but it’s hard. She has a newborn baby in her arms and an older baby crawling on the floor. She’ll have to do the thing she doesn’t want to do. She’ll have to go to the house.

Hazel has skin which matches her name and dark glossy hair, two things which her eldest son John also has. She knocks tentatively on the back door, hoping that the old lady is home. A plump woman wearing a stiff collar and a rigid demeanour appears. Everything about her is old at a time when forty was aged. Her turn of the century clothes, her staid hairstyle, her Victorian opinions. She peers at Hazel round the door frame, her dry face pinched with disapproval.

“I told you not to come to the house,” she says. Her eyes flicker from John, sniffing and shuddering with pain, to newborn baby Paul, clutched tight to Hazel’s thin chest, and beyond her, to the shed at the bottom of the garden. A thin wail can be heard. Baby Susan, who is just thirteen months old.

“I’m sorry, aren’t I,” Hazel says, sounding anything but. “The kid’s hurt his self. Look!” She raises John’s dripping leg, and he lets out another sob. The old lady huffily opens the door and stands aside.

“Yer can clean him up at the sink, there. Be quick about it.”

Hazel enters the spotless kitchen and sits John down on the scrubbed worktop next to the stainless steel sink. The tap runs and John cries. The old lady watches dispassionately from the still open door. “I’ll speak to Jack about this when he comes home from work,” she threatens.

Hazel, with her head turned away from the old lady, allows herself a small smile. The two babies in her arms and the one back in the shed are testament to her relationship with Jack. And while they’re still not married, he might obey his mother by agreeing to stay in the shed so as not to besmirch the reputation of the house, but Hazel knows where she stands in his affections.

She presses a tea-towel gently on John’s knee, where the bleeding finally seems to be stopping. Scooping him up off the counter with one arm, she shifts him onto her hips, aided by his clinging arms which wrap themselves about her slender neck. “You do that,” she mutters, hurrying back down the garden path, back to her other baby, who is now loudly squalling. The shed is a squalid place, but it’s away from the old lady, who watches her leave, her mouth twisted in disgust. “Whore,” she spits, as she slams the door.

John’s youngest sister Deborah is pregnant and so John balances on his knees next to the bed, sharp bones resting on dusty floorboards. He receives his punishment; ten lashes with the belt, strap side, not buckle this time. It was the buckle when Susan fell pregnant two summers ago, but then she was only fifteen, not sixteen like Deborah. John is their big brother and so he should have known. He should have sorted out the “boys what did it.” As the eldest it’s his job to take care of them. It’s his fault, somehow, that the girls have gone astray.

But not everyone thinks that John is failing. The following evening a man in uniform comes to the house evening to speak to Hazel and Jack. John is sixteen and since he left school before his fifteenth birthday, he’s been working in a signal box on the railway. But he dreams of more than this. Dreams of travelling far away from the cramped house where he lives with his parents and siblings. Far away from a place which only offers work on the railway tracks or the railway repair sheds, and almost nothing else.

The man at the recruitment office thinks that John, a quiet and strong, hard working boy, has the potential to make a good marine. He’s come to try and persuade John’s parents to allow him to sign up. He finds only Hazel at home, because Jack is at the pub. He’s visited a few homes like this, in the west end of town. This is the same sort of place which smells of cats, stale cigarettes and yesterday’s greasy dinner. The kind of place where you don’t want to sit down.

“Marines,” Hazel says, with sour derision. “Bloody ridiculous. What will we do without his board?” She smokes without ceasing, regarding the man with the characteristic suspicion of the working class towards anyone in uniform. He doesn’t know that John earns around £4 a week and Hazel takes almost all of it, but he makes an educated guess at the state of affairs by judging the squalor of the place, the endless cigarettes, and the lazy contempt of John’s mother.

“I don’t need much,” John says to the man, with a hint of apology.

The recruitment officer leaves not long after, defeated by ignorance and apathy. He suspects he knows where most of John’s board goes. The woman stinks of gin.

John’s knee rests heavily on the hard ground, no protective clothing or buffer to cushion the impact. He’s left the railway and now works on a building site. A flag stone weighs around 130lbs, and John’s knee takes the full weight as he bends to lift hundreds of them every single day. Up and down ladders he goes, and onto the roof. Bending. Stretching. Bending again. Day after day. Year after year.

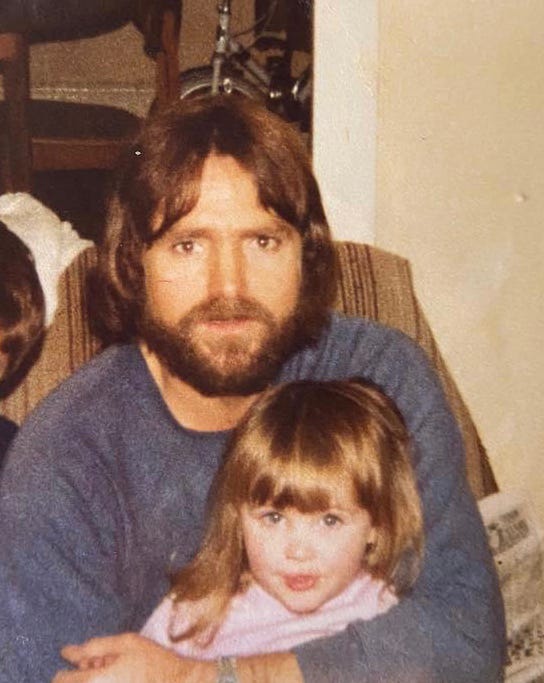

Twenty of them have passed. John’s knee is now a throne for a little girl. The arm-chair where he rests to drink his mug of tea and read his paper is his alone, but they sometimes sit there together when he’s home, which isn’t often because he works long hours. The little girl nestles on his knee, while Des Lynam talks on the telly. She’s enclosed in the safety of his muscly, tattooed arms, which engender a feeling of security no seatbelt ever could. She nestles her nose into the crook of his rough neck and smells salt, Brut and Golden Virginia, and if it’s Sunday and Monday nights, the yeasty tang of Tetley’s bitter.

John’s knee is a ride, where the little girl clings on while he bounces her up and down, making her giggle delightedly. Calloused hands stroke dark blonde strands away from her forehead, rough hands which still never hurt or harm. He has learned a new rhythm of being. A new way to relate. Despite this gentleness, the scars from a damaged childhood can never be fully erased. He loves mostly from afar, not knowing how to come closer, at least not with words, which have never come easily to him.

This hard man who demonstrates love by working all hours and providing whatever she needs, will one day be the father of a writer. The little girl on his knee will take his brooding silences, his emotional absence, and she’ll fill the gaps with her own words, because she knows the things which aren’t spoken out loud are sometimes the most eloquent of all. His silence teaches her to imagine what he might have said, if only he’d known how to say it:

You mean the world to me. Everything I do is for you. I love you.

John’s knee rests heavily on the hard ground, no protective clothing or buffer to cushion the impact. Up and down ladders he goes. Bending. Stretching. Bending again. Day after day. Year after year. Now the knee makes a grinding noise whenever he moves his leg, and this gets louder and more obvious as the years go by.

John never learned how to drive, and so his knee pumps up and down, powering his bike nine miles one way, and then nine miles back. In the rain, in driving winds, in the burning sun. Up and down it goes. Year after year. Synovial fluid diminishes by the day, leaving a joint as desiccated as a parched riverbed during a drought. Bone grinds on bone, and the pain becomes unbearable, an annoyingly constant companion. Sometimes the patella, having lost density and shape, slips out of its position against the femur, and John has to shove it back into place. The agony is nauseating, but he remains uncomplaining, steadfastly walking on until finally, one day, he can walk no more.

He's stooped and has lost inches in height. The little girl who once nestled on his knee, is now a middle aged woman and her powerful dad towers over her no longer. She’s now the same height as him, and the arms which once enclosed her are thinner, the muscles less defined. Solid, oaken branches diminished to driftwood, weathered by sun and sea. What words he had have all but dried up too, some lost because of lack of use, now gone forever, some fallen through the holes in his faltering memory. The little girl, now a woman, remembers for them both.

The aged scar on John’s knee is about the size of a ten pence piece, white and shiny and hairless. It doesn’t tan like the rest of his bowed and brawny legs. It’s a piece of living history, like the scars on his back, an artifact telling the story of the garden in Arthur Street, of a childhood spent in the dust and dirt.

“It’s not severe enough for us to operate, it’s only moderately severe right now,” says the bland-faced doctor. “Try walking. That will help.”

The woman who was once the little girl, stares at the doctor, stunned by this crass response. “He can’t walk,” she says, through gritted teeth. “That’s the entire problem.”

“You could go private,” the doctor casually remarks, turning back to her desktop without waiting for a response. The woman reacts as if she’s received a shock from the door handle of a cheap car. She jerks in her seat and fleetingly imagines a hulk-like scene where she picks up the computer monitor and crowns the doctor’s head with it. The moment passes, leaving sick despair in its wake.

What’s even the point? She thinks. Nobody cares about John. They never did. They didn’t care when he developed pleural plaques in his lungs from all the asbestos he breathed in as a teenager, working on the railways. They didn’t care when the bones in his hands started to crumble from years of manual work in the cold: “well if you will insist on still working,” a callous doctor told him. And they didn’t care when he went deaf after decades of dangerously noisy power tools. Ear defenders? There was no such thing, because when it came to John and other men like him, nobody gave a damn. They still don’t.

This isn’t about John’s knee. John’s lungs. John’s hands. John’s ears. Not really, because the truth is, the whole thing is messed up. Bones crumbling, dry joints grinding, muscles wasting, brain shrinking, skin withering, all gradually turning back to humus before our very eyes. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust, it’s what happens to us all eventually, and if you’ve had a life like John, it will happen to you ten or fifteen years sooner.

No, this is about who matters and who doesn’t. This is about the stink of poverty and how you’re never able to fully wash it off. This is about the unseen boomers, the ones you don’t hear about. The ones who haven’t gobbled up all your housing, and who didn’t feel the benefit of free university education. This is about a man who was born into poverty seventy five years ago, and who has worked his entire life to dig his way out of it, and that no matter how hard he tries, up it comes again, like a turd which won’t flush, reminding him that no matter how far away he travels from that shed on Arthur Street, he still doesn’t matter.

This is Britain in 2025. A place where a man who has dutifully paid into the pot without pause from the age of fourteen until retirement at age seventy-one, cannot get care when he desperately needs it. This is about a society which wants to celebrate freedom without stopping to ensure the most vulnerable are taken care of first. This is about an NHS with diminishing resources which will make cruel economic decisions if it’s not funded adequately, and a society which will allow this to happen as long as the rich and privileged still get to choose.

This is about a man called John, who deserves so much better than this.

Happy Father’s Day Dad.

I love you too.

Brilliant Jayne. My admiration for you goes up another level. I knew you could write beautifully but I don’t think I’ve quite seen this style of writing from you before - the clarity of narration, the emotion, the love, the qualities of really good fiction-writing (and yet of course it’s not fiction, which makes it even better, and sadder). I think you might have a very good novel in you, even if (or because) it’s a thinly veiled true story... Well done and thank you for sharing. Happy Father’s Day.

Beautiful writing Jane, tear provoking and visceral ... You have a rare talent and your dad sounds like a total hero 🥰